-

In June 2010 the Stanford Web Security Research Group released a study of clickjacking countermeasures employed across Alexa Top-500 web sites. It’s an excellent survey of different approaches taken by web developers to prevent their sites from being subsumed by an

iframetag.One interesting point emphasized in the paper is how easily regular expressions can be misused or misunderstood as security filters. Regexes can be used to create positive or negative security models – either match acceptable content (allow listing) or match attack patterns (deny listing). Inadequate regexes lead to more vulnerabilities than just clickjacking.

One of the biggest mistakes made in regex patterns is leaving them unanchored. Anchors determine the span of a pattern’s match against an input string. The

^anchor matches the beginning of a line. The$anchor matches the end of a line.(Just to confuse the situation, when

^appears inside grouping brackets it indicates negation, e.g.[^a]+means match one or more characters that is nota.)Consider the example of the nytimes.com’s

document.referrercheck as shown in Section 3.5 of the Stanford paper. The weak regex is highlighted below:if(window.self != window.top && !document.referrer.match(/https?:\/\/[^?\/]+\.nytimes\.com\//)) { top.location.replace(window.location.pathname); }As the study’s authors point out (and anyone who is using regexes as part of a security or input validation filter should know), the pattern is unanchored and therefore easily bypassed. The site developers intended to check the referrer for links like these:

https://www.nytimes.com/ https://www.nytimes.com/ https://www.nytimes.com/auth/login https://firstlook.blogs.nytimes.com/Since the pattern isn’t anchored, it will look through the entire input string for a match, which leaves the attacker with a simple bypass technique. In the following example, the pattern matches the text in red – clearly not the developers’ intent:

https://evil.lair/clickjack.html?a=https://www.nytimes.com/The devs wanted to match a URI whose domain included “.nytimes.com”, but the pattern would match anywhere within the referrer string.

The regex would be improved by requiring the pattern to begin at the first character of the input string. The new, anchored pattern would look more like this:

^https:\/\/[^?\/]+\.nytimes\.com\/The same concept applies to input validation for form fields and URI parameters. Imagine a web developer, we’ll call him Wilberforce for alliterative purposes, who wishes to validate U.S. zip codes submitted in credit card forms. The simplest pattern would check for five digits, using any of these approaches:

[0-9]{5} \d{5} [[:digit:]]{5}At first glance the pattern works. Wilberforce even tests some basic XSS and SQL injection attacks with nefarious payloads like and

'OR 19=19. The regex rejects them all.Then our attacker, let’s call her Agatha, happens to come by the site. She’s a little savvier and, whether or not she knows exactly what the validation pattern looks like, tries a few malicious zip codes (the five digits are underlined):

90210' alert(0x42)57732 10118alert(0x42)Poor Wilberforce’s unanchored pattern finds a matching string in all three cases, thereby allowing the malicious content through the filter and enabling Agatha to compromise the site. If the pattern had been anchored to match the complete input string from beginning to end then the filter wouldn’t have failed so spectacularly:

^\d{5}$Unravelling Strings

Even basic string-matching approaches can fall victim to the unanchored problem; after all they’re nothing more than regex patterns without the syntax for wildcards, alternation, and grouping. Let’s go back to the Stanford paper for an example of walmart.com’s

document.referrercheck based on a JavaScript String object’sIndexOffunction. This function returns the first position in the input string of the argument or -1 in case the argument isn’t found:if(top.location != location) { if(document.referrer && document.referrer.indexOf("walmart.com") == -1) { top.location.replace(document.location.href); } }Sigh. As long as the

document.referrercontains the string “walmart.com” the anti-framing code won’t trigger. For Agatha, the bypass is as simple as putting her booby-trapped clickjacking page on a site with a domain name like “walmart.com.evil.lair” or maybe using a URI fragment, https://evil.lair/clickjack.html#walmart.com. The developers neglected to ensure that the host from the referrer URI ends in walmart.com rather than merely contains walmart.com.The previous sentence is very important. The referrer string isn’t supposed to end in walmart.com, the referrer’s host is supposed to end with that domain. That’s an important distinction considering the bypass techniques we’ve already mentioned:

https://walmart.com.evil.lair/clickjack.html https://evil.lair/clickjack.html#walmart.com https://evil.lair/clickjack.html?a=walmart.comPrefer Parsers Before Patterns

Input validation filters often require an understanding of a data type’s grammar. Sometimes this is simple, such as a five digit zip code (assuming it’s a US zip code and assuming it’s not a zip+4 format). More complex cases, such as email addresses and URIs, require that the input string be parsed before pattern matching is applied.

The previous

indexOfstring example failed because it doesn’t actually parse the referrer’s URI; it just looks for the presence of a string. The regex pattern in the nytimes.com example was superior because it at least tried to understand the URI grammar by matching content between the URI’s scheme (http or https) and the first slash (/)1.A good security filter must understand the context of the pattern to be matched. The improved walmart.com referrer check is shown below. Notice that the

get_hostname_from_urlfunction now uses a regex to extract the host name from the referrer’s URI and the string comparison ensures the host name either exactly matches or ends with “walmart.com”.(You could quibble that the regex in

get_hostname_from_urlisn’t anchored, but in this case the pattern works because it’s not possible to smuggle malicious content inside the URI’s scheme. The pattern would fail if it returned the last match instead of the first match. And, yes, the typo in the comment in thekillFramesfunction is in the original JavaScript.)function killFrames() { if(top.location != location) { if(document.referrer) { var referrerHostname = get_hostname_from_url(document.referrer); var strLength = referrerHostname.length; if((strLength == 11) && (referrerHostname != "walmart.com")) { // to take care of https://walmart.com url - length of "walmart.com" string is 11. top.location.replace(document.location.href); } else if(strLength != 11 && referrerHostname.substring(referrerHostname.length - 12) != ".walmart.com") { // length of ".walmart.com" string is 12. top.location.replace(document.location.href); } } } } function get_hostname_from_url(url) { return url.match(/:\/\/(.[^/?]+)/)[1]; }Conclusion

Regexes and string matching functions are ubiquitous throughout web applications. If you’re implementing security filters with these functions, keep these points in mind:

Normalize the character set – Ensure the string functions and regex patterns match the character encoding, e.g. multi-byte string functions for multi-byte sequences.

Always match the entire input string – Anchor patterns to the start (

^) and end ($) of input strings. If you expect input strings to include multiple lines, understand how multiline(?m)and single line(?s)flags will affect the pattern. If you’re not sure then explicitly treat it as a single line. Where appropriate to the context, the results of string matching functions should be tested to see if the match occurred at the beginning, within, or at the end of a string.Prefer a positive security model over a negative one – Define what you want to explicitly accept rather than what to reject.

Allow content that you expect to receive and deny anything that doesn’t fit – Allow list filters should be as strict as possible to avoid incorrectly matching malicious content. If you go the route of deny listing content, make the patterns as lenient as possible to better match unexpected scenarios – an attacker may have an encoding technique or JavaScript trick you’ve never heard of.

Use a parser instead of a regex – If you want to match a URI attribute, make sure your pattern extracts the right value. URIs can be complex. If you’re trying to use regexes to parse HTML content…good luck.

Don’t shy away from regexes because their syntax looks daunting, just remember to test your patterns against a wide array of both malicious and valid input strings.

But do avoid regexes if you’re parsing complex grammars like HTML and URLs.

• • • -

In January 2003 Jeremiah Grossman disclosed a technique to bypass the HttpOnly1 cookie restriction. He named it Cross-Site Tracing (XST), unwittingly starting a trend to attach “cross-site” to as many web-related vulns as possible.

Unfortunately, the “XS” in XST evokes similarity to XSS (Cross-Site Scripting) which often leads to a mistaken belief that XST is a method for injecting JavaScript. (Thankfully, character encoding attacks have avoided the term Cross-Site Unicode, XSU.) Although XST attacks rely on JavaScript to exploit the flaw, the underlying problem is not the injection of JavaScript. XST is a technique for accessing headers normally restricted from JavaScript.

Confused yet?

First, let’s review XSS and HTML injection. These vulns occur because a web app echoes an attacker’s payload within the HTTP response body – the HTML. This enables the attacker to modify a page’s DOM by injecting characters that affect the HTML’s layout, such as adding spurious characters like brackets (

<and>) and quotes ('and").Cross-site tracing relies on HTML injection to craft an exploit within the victim’s browser, but this implies that an attacker already has the capability to execute JavaScript. Thus, XST isn’t about injecting

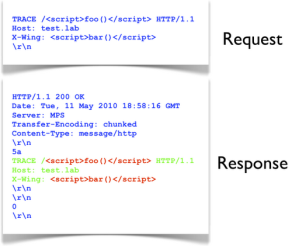

<script>tags into the browser. The attacker must already be able to do that.Cross-site tracing takes advantage of the fact that a web server should reflect the client’s HTTP message in its respose.2 The common misunderstanding of an XST attack’s goal is that it uses a TRACE request to cause the server to reflect JavaScript in the HTTP response body that the browser would then execute. In the following example, the reflection of JavaScript isn’t the real vuln – the server is acting according to spec. The green and red text indicates the response body. The request was made with netcat.

The reflection of

<script>tags is immaterial (the RFC even says the server should reflect the request without modification). The real outcome of an XST attack is that it exposes HTTP headers normally inaccessible to JavaScript.To reiterate: XST attacks use the

TRACE(or synonymousTRACK) method to read HTTP headers that are otherwise blocked from JavaScript access.For example, the

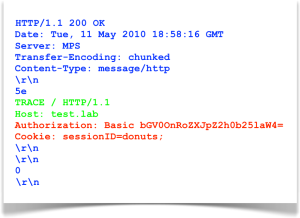

HttpOnlyattribute of a cookie prevents JavaScript from reading that cookie’s properties. TheAuthenticationheader, which for HTTP Basic Auth is simply the Base64-encoded username and password, is not part of the DOM and not directly readable by JavaScript.No cookie values or auth headers showed up when we made the example request via netcat because we didn’t include any. Netcat doesn’t have the internal state or default headers that a browser does. For comparison, take a look at the server’s response when a browser’s XHR object makes a

TRACErequest. This is the snippet of JavaScript:var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest(); xhr.open('TRACE', 'https://test.lab/', false); xhr.send(null); if(200 == xhr.status) alert(xhr.responseText);The following image shows one possible response. (In this scenario, we’ve imagined a site for which the browser has some prior context, including cookies and a login with HTTP Basic Auth.) Notice the text in red. The browser included the

AuthorizationandCookieheaders to the XHR request, which have been reflected by the server:

Now we see that both an HTTP Basic Authentication header and a cookie value appear in the response text. A simple JavaScript regex could extract these values, bypassing the normal restrictions imposed on script access to headers and protected cookies. The drawback for attackers is that modern browsers (such as the ones that have moved into this decade) are savvy enough to block

TRACErequests through the XMLHttpRequest object, which leaves the attacker to look for alternate vectors like Flash plug-ins (which are also now gone from modern browsers).This is the real vuln associated with cross-site tracing – peeking at header values. The exploit would be impossible without the ability to inject JavaScript in the first place3. Therefore, its real impact (or threat, depending on how you define these terms) is exposing sensitive header data. Hence, alternate names for XST could be TRACE disclosure, TRACE header reflection, TRACE method injection (TMI), or TRACE header & cookie (THC) attack.

We’ll see if any of those actually catch on for the next OWASP Top 10 list.

-

HttpOnly was introduced by Microsoft in Internet Explorer 6 Service Pack 1, which they released September 9, 2002. It was created to mitigate, not block, XSS exploits that explicitly attacked cookie values. It wasn’t a method for preventing html injection (aka cross-site scripting or XSS) vulns from occurring in the first place. Mozilla magnanimously adopted in it FireFox 2.0.0.5 four and a half years later. ↩

-

Section 9.8 of the HTTP/1.1 RFC. ↩

-

Security always has nuance. A request like

TRACE /<script>alert(42)</script> HTTP/1.0might be logged. If a log parsing tool renders requests like this to a web page without encoding it correctly, then HTML injection once again becomes possible. This is often referred to as second order XSS – when a payload is injected via one application, stored, then rendered by a different one. ↩

• • • -

-

When a day that you happen to know is Wednesday starts off by sounding like Sunday, there is something seriously wrong somewhere.

Bill Masen’s day only worsens as he tries to survive the apocalyptic onslaught of ambling, venomous plants.

John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids doesn’t feel like an outdated menace even though the book was published in 1951.

It starts as the main character, Bill Masen, awakens in a hospital with his eyes covered in bandages. It’s a great hook that leads to a brief history of the triffids while also establishing an unease from the start. The movie 28 Days Later uses an almost identical method to bring both the character and audience into the action.

I love these sorts of stories. Where Cormac McCarthy’s The Road focuses on the harshness of personal survival and meaning after an apocalypse, Triffids considers how a society might try to emerge from one.

The 1981 BBC series stays very close the book’s plot and pacing. Read the book first, as the time-capsule aspect of the mini-series might distract you – 80s hair styles, clunky control panels, and lens flares.

But if you’re a sci-fi fan who’s been devoted to Doctor Who since the Tom Baker era (or before), you’ll feel right at home in the BBC’s adaptation.

• • •